Prometheus in the Pacific

80 years ago my great-uncle watched the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay, but he did not survive the war

Eighty years ago today, on September 2nd, 1945, my great-uncle, the naval combat artist Mitchell Jamieson, was onboard the USS Missouri for the formal surrender ceremony which ended WWII. Mitchell had been in the Pacific since March of that year when he was sent to document Okinawa, one of the war’s bloodiest battles, and paint the decimated battleground of Iwo Jima.

He was at sea on August 6th, 1945, and first learned that the atomic bomb had been dropped from a shipboard announcement. Three days later, he wrote to Robert Parsons, the officer in charge of the Navy Combat Art Section, back in Washington, DC:

Everyone’s excited here about the atomic bomb and Russia’s entry into the war and there’s no end of discussion and optimistic predictions…. the hammer blows are raining one after the other and no one can be in this area without being overwhelmed practically by the volume of activity everywhere.

On August 29th, he wrote to Parsons again, this time from a ship only miles from mainland Japan:

We’ve just entered the inner Tokyo Bay– I had the good fortune to get in with spearhead fleet units … This has all happened so quickly it all seems quite unreal – yet there is Fujiyama (Mt. Fuji) before our eyes!

Mitchell’s enthusiasm for the end of the war, and his disbelief that it was actually happening, were understandable. Selected as one of eight Naval combat artists, he entered training in September 1942, when he was just 26 years old. By the time he arrived in the Pacific, he’d been at the invasion of Sicily, where men all around him were hit with shrapnel, and captured the brutality of D-Day in his sketchbooks while living in a foxhole on the beaches of Normandy.

For three years he’d traversed the globe, witnessing and drawing heroism and bravery, and thousands of casualties and deaths. On June 12, 1945, he wrote to Parsons again, in regards to the challenges that he and another combat artist friend were coming up against in the field:

As I myself have discovered, it’s tough enough to undergo a campaign but on top of that to concentrate on making drawings from your experience can be really wearing.

During the epic 82-day Battle of Okinawa, nicknamed “Typhoon of Steel,” Mitchell had been embedded with the 6th Division, as they made their way into the interior of the island, dodging bullets from concealed snipers. Accompanying the hundreds of pieces that are collected by the Naval History and Heritage Command, where the majority of his wartime work is housed, are “captions” he wrote about what he was depicting. Some of these are basic descriptions, but others are short essays, poignant evocations of what he was seeing and experiencing with his artist’s eye.

For his painting “The Foxholes– Okinawa” he added this lyrical description, which powerfully captures the interminable march and constant anxiety of life in a war-zone:

In a hole like this at night your furniture is rifle and bayonet, blanket and poncho; best comforts of a carefully shielded cigarette and a bar of K ration chocolate, best way of taking your mind off the cold and discomfort; sorting out the traffic passing overhead into mortars, naval shells, shell from field guns and unmistakable rifle and machine gun fire.

Now it is early morning and all firing has ceased for a while, for some reason. You can light a cigarette without being too careful now and regard the dim forms of sleeping companions a few minutes before a low flying hellcat breaks the spell and it is time to rise stiffly and start another long day all over again.

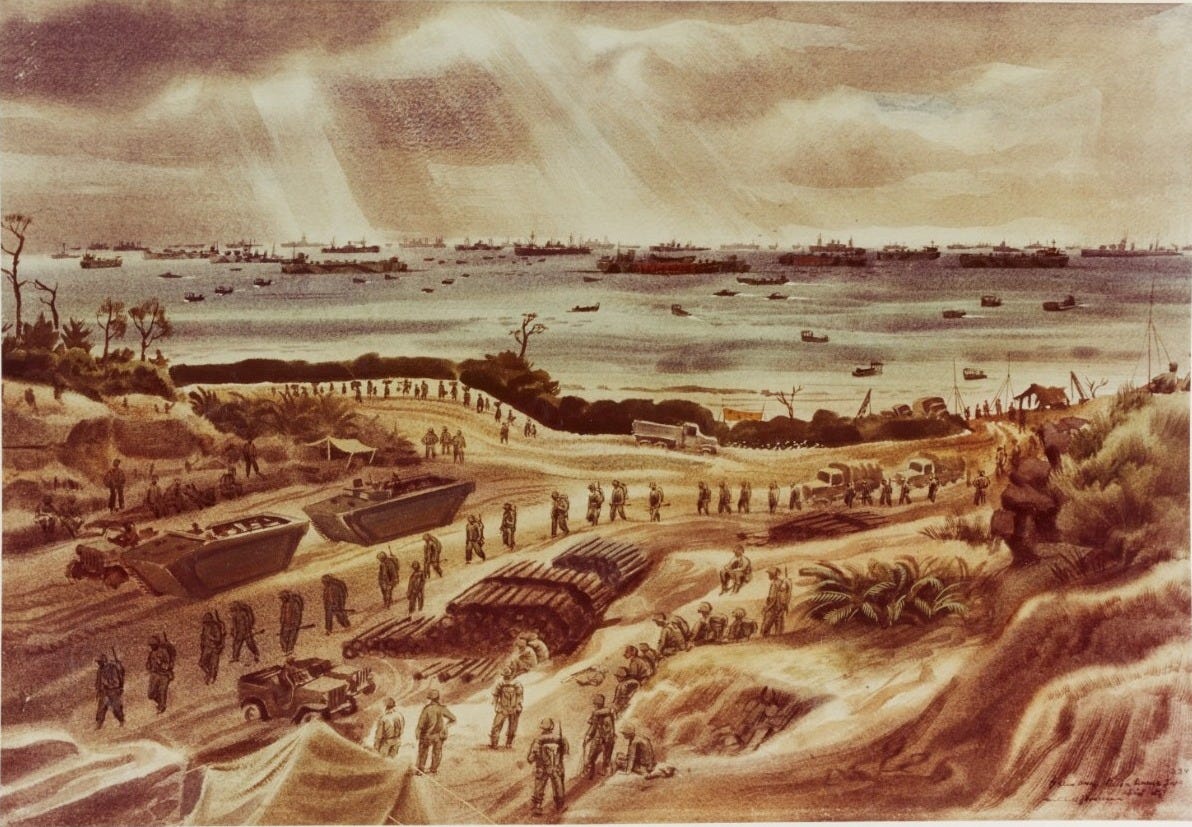

In Okinawa, he also witnessed one of the most violent assaults on civilians in modern warfare. As many as 150,000 Okinawans were killed during the battle, and he painted terrified women pleading for their lives, evacuated groups sitting with their belongings, burning villages. The caption for his painting,“D-Day Plus One– Green Beach Two,” contrasts the successful incursion of the infantry with the massive displacement of the population:

From here there is not only the positive surging force of the main dramatic theme but also those melancholy bits of embroidery in a minor key, faintly heard crossing and recrossing the powerful current– homeless civilians carting off what little they have left out of a holocaust of shelling and bombing… to temporary refugee camps until shelter can be found and military government established.

Over the next few decades, Mitchell’s view on war and the Atomic Age shifted dramatically. The metaphor of Prometheus, who, in Greek mythology, was punished for stealing fire from the gods to give it to humans, appeared almost immediately after the bombs were dropped in 1945 (and again recently with the publication of Oppenheimer’s biography, American Prometheus). In 1961, Mitchell picked up on this imagery in a mural he painted called simply, “Prometheus,” which was a direct reference to the first atomic detonation in New Mexico.

His perspective on war continued to darken, notably after a brief 1967 trip to Vietnam as a civilian combat artist. His “Plague Series,” done in the last years of his life, exposed the savagery of the Vietnam War in grim black and white prints. He obsessively created hundreds of pieces about Vietnam, many of which echo his drawings of Okinawan refugees. Clearly he recognized the connection between these groups, from different countries and times, caught in the same unconscionable violence they did not choose and could not escape.

About the Plague series, Mitchell stated his intention to convey a “vision of the war as simply the most violent manifestation of a spreading and profound spiritual plague.” Recognizing the senseless nature of this kind of blind ferocity, he wrote: “The plague makes no distinction between victims and executioners.”

Mitchell took his own life in 1976, and I wonder if he counted himself in this equation. The US had won the war; he had been there to witness the surrender. And yet, its impacts continued to reverberate in his life, influencing his artwork, his career, his relationships. He too was a victim, though no one recognized this until it was too late.

My great-uncle may have escaped dying in war, but there can be no doubt that he died of war.

This is a beautiful and poignant tribute to your great uncle Kathie. Thank you! We will never talk enough, write enough, protest enough against the absurdity of wars and the lasting devastating consequences it inflicts at all levels. 😘

I have just re-read this remarkable account of your uncle, astonishing for his skills as combat artist and eloquent accounts of the successive horrors on so many fronts, all over the world. A wonderful piece—thank you!